Canadian Officers Notes On “British Army Manoeuvres” Sept. 16th – 19th, 1912. Part II.

PART II.

MISCELLANEOUS INFORMATION ON BRITISH DIVISIONAL MANOEUVRES, ARMAMENT, TRAINING AND AUXILIARY SERVICES.

THE CAVALRY.

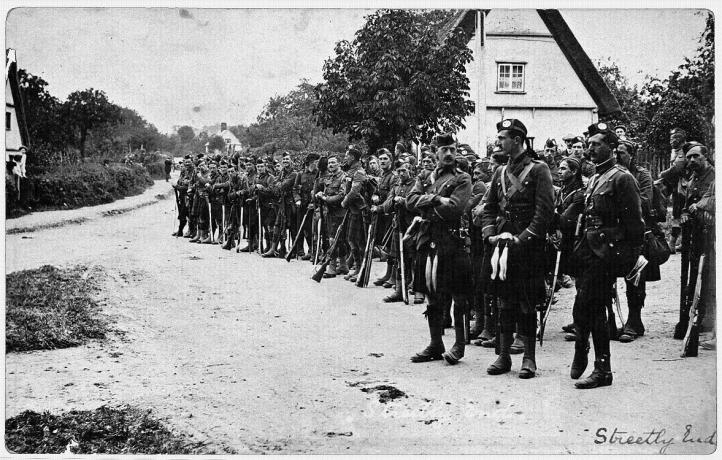

During the Cavalry manoeuvres north of Windsor preceding the inter-divisional manoeuvres, the Southern force of three brigades under General Allenby operated against a skeleton White force. General Allenby’s division was armed with the short rifle, sword and lance. The operations commenced with swimming the horses across the Thames River at several points above Windsor. The river at the time was nearly 100 yards wide, with a fairly strong current, being in flood with the heavy rains. The saddlery was sent across in boats. The method of crossing the horses was to attach them by their halters to an endless picket rope extending across the river and back again. Parties of men on either shore “walked away” with the slack at the word of command, and the horses, tied at intervals of 10 or 12 feet along the rope, were partly dragged and partly swam across the river. All that is necessary to ensure success is a good “take-off” and a good landing on either shore. The brigades crossed without accident.

During the ensuing operations lasting about a week, officers and men maintained the same energy and alertness as though on active service. It was difficult country to scout, owing to the numerous lanes and high hedges, and gave little scope for the exercise of the cavalry spirit in the minor engagements that marked the operations, dismounted action with rifles being the rule. During inter-divisional manoeuvres only Divisional Cavalry and a few cyclists were present, consequently both Commanders had difficulty in carrying out tactical reconnaissances of the hostile force. By means of air-craft the general situation was fairly well known to each Commander, but not the local situation when tactical contact was made. In the absence of definite information in enclosed country neither Commander appeared inclined to pursue energetic measures against his opponent. It was noticeable during all the manoeuvres that few opportunities presented themselves for mounted action by the cavalry in large bodies. No doubt the nature of the country had a good deal to do with the prevalent employment of cavalry in dismounted work; but it would seem that this arm in large bodies would have to watch its opportunities for mounted action when the terrain is suitable.

ARTILLERY.

The employment of mobile artillery as demonstrated at the manoeuvres left little to be suggested in the way of improvement of the system of training in Canada. For firing and manoeuvre the Canadian artillery has at Petawawa a training area not surpassed in the world either for extent or suitability. It is therefore to be expected that the Canadian artillery should be fairly well trained in manoeuvre, long and medium range fire and the selecting of positions. With us comparatively little training or ammunition is devoted to the practice of “close support” and decisive ranges. This is to some extent due to the fact that hitherto there have been few opportunities for combined training at Petawawa, and the further fact that having been trained in the more difficult phases of producing fire effect, battery commanders need comparatively little additional practice to ensure results at decisive ranges.

During the inter-divisional, as well as the army manoeuvres, Canadian artillerists would have been struck with the extent to which batteries and brigades went into action in the open at practically all ranges. Where cover was available, either from fire or view, it was almost invariably taken advantage of by the gunners of both forces. But the fact apparently has to be recognized that where large bodies of troops are engaged there will be not, under ordinary conditions, be nearly enough covered positions for the proportionate number of guns. Consequently the peremptory necessities of getting the guns into the fight, to give the infantry the support they are entitled to expect, render it imperative that many batteries and brigades will have to deploy in the open not only for “close support” but at the medium ranges. In other words, to be of use guns have to get into action; if there are not enough covered positions to go round, as is most likely to be the case, then the guns will have to take to the open.

In the final phase of the battle on the last day of the Army manoeuvres at least half the guns were in the open, otherwise they could not have taken part in the fight. Perhaps the moral is that when large forces are engaged even under the conditions of a modern battlefield, the targets offered are sure to be so tempting as to justify considerable freedom of exposure on the part of the artillery in order to take advantage of them. The Canadian system of training closely follows that of the British and is quite up-to-date. There are few changes to be noted. The advent of the aeroplanes forces upon artillery commanders the additional desirability of over-head cover from view afforded by woods, either when halted or in action. The new goniometric sight which has been placed on the latest types of field guns in the factories is supported by a triangular 3-inch steel stem, fitting into a heavy socket on the gun carriage, so as to ensure the necessary rigidity, as compared with the proposal to attach it to the shield by a bracket. The stem can be run up to the level of the top of the shield.

The gun manufacturing companies have some excellent types of automatic field guns with block-breech action, which, if the ammunition supply question could be successfully solved, would undoubtedly give a high rate of gun fire. In addition to heavy mobile guns for enfilade purposes, there were in use at the manoeuvres several batteries of heavy howitzers capable of throwing large projectiles to a considerable distance. The Blue Army placed one of these batteries on a hill north of Cambridge for the purpose of protecting its left flank from a turning movement, during a short but critical period in the preliminary operations. Field Howitzers were pushed well forward under cover of woods during many of the engagements and came into action at close range. The 60-pounder guns of the heavy artillery were able to find good positions during the main engagement on the last day of the army manoeuvres, which enabled them to bring cross-fire to bear against different portions of the hostile lines of artillery and infantry. During the preliminary operations these heavy guns marched in rear of the troops of their own division. It was rather significant that the field artillery only put three guns and three wagons per battery in the field during the manoeuvres, owing to the low peace establishment of horses.

INFANTRY.

The march discipline of the Infantry was particularly noticeable, the columns were invariably well closed up, while the right half of the road was kept clear for the passage of traffic past the columns.

Deployments for attack were very varied according to the ground. There were usually several extended lines in order to obtain depth in the attack. Sometimes these lines were in echelon, sometimes in column if there was not sufficient frontage allotted to enable them to extend into echelon. Full use of cover was made where this was available, but if none was at hand it was not considered impossible to advance over open ground in extended order, provided that the advance was covered by artillery fire or infantry fire from neighbouring bodies of troops. The principal lessons to be learnt by the Infantry of the Canadian Militia from these manoeuvres are the vital necessity of march discipline, by means of which the infantry soldier can be brought into action with the minimum of fatigue and confusion; the necessity of practising deployments to come into action with the least delay in encounter combats, which must be frequent in enclosed country; the need of covering fire, either gun or rifle, in advancing over open ground in the attack; and lastly, the necessity of depth in formation so as to bring a sufficient number of rifles into the firing line before the assault can be carried out.

There is another phase of infantry work which is becoming increasingly important and which could be conveniently practised by our city regiments as well as the camping corps. This is night operations, consisting of night marches, night advances and night attacks. During the inter-divisional manoeuvres the Canadian officers took part in one of these operations, consisting of a night advance by the 1st Division, followed by a deployment for attack at dawn. The Division moved out of its bivouac at 9.30 p.m. and marched nine miles to the place of rendezvous, where a halt was made in thick woods until the column was closed up, orders prepared and issued and the men rested. Shortly after midnight the column moved off, wheeled transport being kept in rear. An advance guard of one company preceded the column by about 100 yards until the outposts were reached, three miles to the front.

After passing the outposts a Brigade was deployed along a front of a mile and a half, as nearly as could be judged in the darkness. The infantry lay down and waited until early dawn when the attack was launched. Such operations require a good deal of preliminary staff work, as well as practice on the part of the troops, in order to carry them out successfully. This training could be well carried out by our city regiments during the drill season in preparation to co-operate with the other arms when they go into camp under the new system inaugurated last year. Such practices could also be usefully combined with instruction in night outposts. The Territorial Infantry during the army manoeuvres were not allotted a very active role. For the defence of Cambridge they prepared a defensive position and threw out an outpost line. During the last day the detachment was ordered to Bartlow to join in the final engagement, but owing to the block of traffic on the road from Cambridge it was late in the afternoon before the Territorial Brigade was able to come into action: the attack was directed against a flank of the opposing troops, and succeeded in doubling them back at right angles to their original line of attack. Being a selected Brigade of Infantry from the Territorial force, both officers and men appeared to realize that they were on trial alongside the regular troops, and they created a good impression among the Canadian officers from the way they carried out the task entrusted to them.

CO-OPERATION BETWEEN ARMS.

Between Artillery and Infantry close communication was kept by telephone, visual signalling, mounted and cyclist orderlies. The senior artillery officer usually accompanied the commander under whom he was serving directly. With small forces told off for a particular task the artillery were usually placed under the Infantry Brigadier. With larger forces, such as a Division, the O.C., R.A., retained control of the guns in the Division, and allotted tasks according to the infantry situation under instructions from the Divisional Commander. The Cavalry Divisions worked invariably under the direct control of the Army Commander, and rarely co-operated closely with the troops in the Divisions. On the other hand it was the exception for the troops in the Division to support the work done by the Cavalry, even though as in one instance, a mixed brigade was placed at the disposal of the Cavalry Commander. The cyclists, however, were able on several occasions to co-operate with the cavalry. It would appear that during the preliminary phases the cavalry by their mobility outstrip the supporting infantry and field artillery, and cannot delay action until their arrival when touch with the enemy is gained. It is only in the case of a reverse that the cavalry would use the slow moving support as a rallying point. During the main engagement the employment of a mass of cavalry wide on one flank appeared to lead only to indecisive results.

CYCLISTS.

About 2,500 cyclists were detailed from Territorial Cyclist Battalions, under the Cavalry Commanders on either side. There being numerous good cycling roads, both main roads and country lanes, all over the manoeuvre area, the cyclist units were able to give very effective support to the cavalry by their mobility and fire action. They relieved the cavalry of a large portion of harassing outpost and patrol duties on the roads and were able on several occasions to influence the local situation by fire action. The quickness with which they could come into action, the possibility of sending every rifle into the firing line, and their mobility on the roads clear of troops in front of the main columns were points which drew particular attention. On the other hand in case of being driven back there is the possibility of the cycles being captured, as it is impossible to move the machines once the cyclists have deployed. The necessity of march discipline to prevent undue opening out of a column of cyclists was apparent. It has to be remembered, however, that numerous and good roads are a necessity for the effective employment of cyclists. Motor cyclists were largely employed with success as messengers, principally for the directing staff, umpire staff, and for communication between the cavalry divisions and army headquarters; they were not employed on combatant duties, except for the transportation of machine guns. Motor cyclists were able to travel at a rate of at least 40 miles an hour.

MACHINE GUNS.

There is a marked increase of interest in machine guns, both as to their construction and tactical employment. All the larger Arm companies have perfected patterns, each of which is represented as embodying some essential improvement. The result is that the present weapons of this class exhibit a marked advance in simplicity of mechanism, fire effectiveness and facility of transportation. Some are fed by clips containing 25 or more cartridges, others still retain the belt feed. They are variously transported,—on pack-saddles, in limbered carts drawn by horse or hand, on their carriages attached to small limbers, or even on motor-cycles and on automobiles. The firing tripods have been much improved, so as to be rapidly adjustable for the sitting, kneeling or prone positions, and can also be reared against the reverse side of a trench or wall in order to fire over it. At the Hythe School of Musketry interesting experiments are being made in brigading machine guns and handling them as a tactical unit somewhat on the lines of a battery of artillery. What may be termed the method of manoeuvre and the fire discipline are modelled on the artillery.

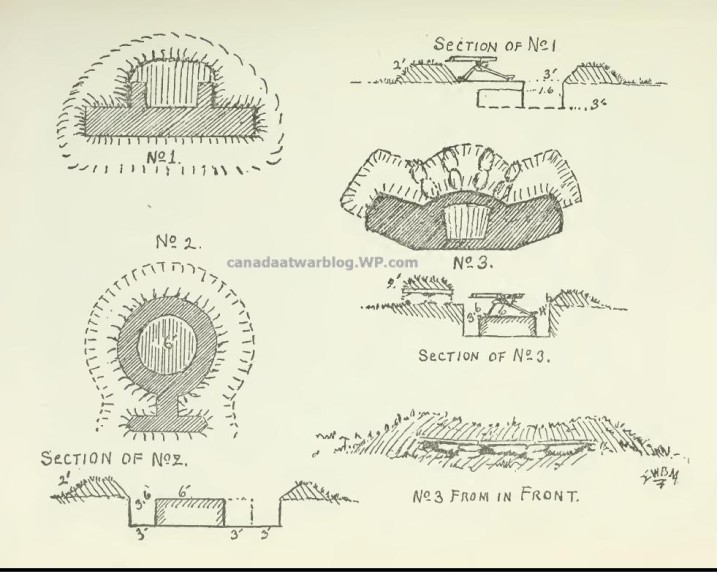

The unit now being experimented with consists of 8 guns. The guns are brought up under cover to a semi-crest position, where they are unpacked and placed on their tripods. The Officer Commanding makes his preliminary observation of the enemy’s position, estimates the range and gives it out as an order to the group of guns. In giving the range the “ladder” method is issued, i.e., each pair of guns is given an increasing distance, as 850,950, 1,050, 1,150 yards. This has the double advantage of getting the most effective range and “searching” at the same time. The guns being in readiness, the command ‘in action’ is given and three men lift each gun with its tripod and run up to the crest. As each gun is laid the noncom, holds up his hand and when all are ready, the signal is given to commence firing. In the same way the guns can “sweep” or be allotted sections of the target. This system could be used for the brigading of regimental machine guns; also, it would be worth considering, whether one or more such independent units under the immediate control of the infantry brigade commander could not be used with great advantage as a mobile reserve in addition to the regimental machine guns. At Hythe there are also various models of hasty entrenchments for machine guns, as shown in the diagram:

SMALL ARMS AND MUSKETRY.

New Service Rifle.—The new service rifle was inspected at Enfield. It has a calibre of .276, weighs 8 pounds 12 ounces to 9 pounds, has a barrel 2G inches long and a magazine which holds five rounds. Subsequently one of the party was permitted to strip and examine the parts of the rifle; but the details are at present of a confidential nature. It may, however, be mentioned that the rifling is an entirely new departure.

- A. Ammunition.—At Woolwich it was learned that experiments have been made recently in altering the mixture of the alloy for the jacket of the small arm bullet so as to lessen the possibility of nickel fouling in rifle barrels. The only ammunition which has been manufactured for the army during the past two years has been the Mark VII with the pointed (or Spitzen) bullet. All ammunition is now made up in chargers containing five rounds each. These chargers are put up in packets containing four, which are placed in cheap cotton bandoliers, which, in peace, can be refilled, and in war can be thrown away. These bandoliers are packed in boxes containing a thousand rounds.

Musketry Training.—During recent years the musketry at the School of Musketry at Hythe has undergone great improvements. Judging distance and fire discipline are mostly carried out at ranges varying from 800 to 1,500 yards. A class of eighty officers and N.C.O.’s were seen undergoing training according to the new system. The class was divided into sections, and each member of a section took command in turn. A man appeared at some point in the distance, and the Section Commander gave his orders to the section, describing the position of the target and the distance. For instance, if the target was near some distinctive object such as a Martello tower or a sand heap, the Section Commander would extend his arm, elevate one or more fingers and say: “Man one (2 or 3) fingers right (or left) of such an object at yards rounds rapid (or independent) fire (or volleys)”. The commands, direction and distance given were carefully noted by the instructors, and when the firing ceased the distance was measured by a range finder and corrected. The practice taught three things:—

- 1st. Judging distance.

- 2nd. Correct description of target and direction.

- 3rd. Fire control.

No bull’s-eye targets were employed during these practices, figure targets being used instead. Everything seemed to be designed to make the work as realistic as possible, approximating service conditions.

Range Finders.—The range finders used were the Marindin and Barrs Stroud, a preference being expressed for the latter instrument owing to the fact that a slight blow would bend the Marindin, thus throwing the lenses out of focus. On the other hand the Barrs Stroud may be bent to a considerable angle and still give serviceable readings. However, the latter instrument has the disadvantage of being more affected by the variations in temperature.

Thirty Yard Target.—One feature of the instruction was particularly attractive, and a good deal of interest was shown in it by a class of Territorial officers. This was the thirty yard range practice, which could readily be widely introduced in Canada and would soon become popular when understood. The following is a brief description of it: A substantial wall was erected some ten or twelve feet high and about twenty-feet long. In front of this was a bank of earth, and in front of the earth a small landscape picture representing a country scene as it would be viewed from a distance of 800 to 1,500 yards. Above the landscape picture was a paper screen two or three feet high. A similar landscape was painted on a small board with a handle for the use of the instructor. The instructor inserted a pin in the picture at a point against which he wished the fire to be directed. Sometimes, to make the practice still more realistic a paper drawing of a gun of a unit, the size it would appear to the eye at the distance named, was pinned on the landscape for a target.

When the preliminary arrangements were completed, the section commander gave his orders in the following manner: ‘Haystack corner of field on the right towards Battery behind river.—Rapid (or other) fire, rounds at (say) 1,400 yards.’ The sights were raised to the elevation given and the firing commenced. When the fire ceased, the squad closed up to the target and the instructor measured above the target named to a point on the paper screen by a scale graduate to the distance—say, two feet above for 1,400 yards. He then drew a line horizontally across the paper screen indicating the height at which the shot should have struck. A wire screen five inches square was then laid on the paper screen over the spot which should have been the point of impact, and all shots within this square counted five points. All shots outside of the square were penalized by a deduction of two points from the total. Interest was much stimulated not only in the shooting but by the possibility that one or more members of the squad might mistake the proper target and thereby greatly damage the score of their comrades. Each member of the squad as he assumed command tried to beat previous scores and in this way the interest in the practice was sustained throughout. It seemed to be a great improvement on miniature range firing at conventional targets.

TRANSPORT AND SUPPLY.

Mechanical transport was more extensively used than at any former manoeuvres, and the numerous excellent roads in nearly all parts of the manoeuvre area contributed to the success of the experiment. As during the period when the roads in Canada are in approximately as good condition, mechanical transport could be used to the same extent, a brief description of the method of supplying a division on the march may be of interest.

Each division had sixteen steam motor trucks, each with a capacity of five tons, allotted to it. There was also one reserve truck and one repair truck. Taking the case of one division as an example: Two trains of five and nine cars respectively arrived at railhead at 5.30 a.m. and noon with food and forage. The motor transport loaded these supplies and carried them forward to replenish the divisional train the same evening. The latter, composed of horse transport, distributed to the units. If railhead advanced with each day’s march the motor transport would wait at the advanced base of the previous day. If railhead did not advance, presumably another corps of mechanical transport would be sent out from railhead to connect with the first sent forward, though this, of course, was not necessary during the manoeuvres. On some days the troops marched 25 to 30 miles and but little difficulty was experienced in keeping them supplied, except when bivouacs were established after dusk, when the divisional trains could not always locate the units.

On service it is usual for troops of a division to always bivouac relatively in the same order, as far as possible, at every halt, so this difficulty is avoided. The waggons used were chiefly of the ordinary G. S. type, though much of the hired transport consisted of covered vans such as are used for moving furniture, which were well suited for the prevailing weather. Small limbered wagons are used with the first line transport. They are simply two small wagon bodies joined by a perch, which enables them to travel better over rough ground. As against this it is difficult to keep the loads well balanced, and there is a waste of carrying capacity in proportion to horse-power used. The units are accompanied on the march by water carts fitted with filters. The best type of filter has not yet been decided upon, but the remedy of such defects as exist is under consideration.

The use of travelling cookers was general during the operations and the results were excellent. During the inter-divisional manoeuvres the weather was cold and wet, and the troops frequently bivouacked at night, after a long march, under the most trying conditions. While the physique and spirit of the troops were excellent and they endured real hardships with admirable cheerfulness, it is doubtful if the sick list would have been kept normal had it not been for the hot rations furnished under all conditions of weather from these portable cookers. They may be briefly described as sheet-iron cauldrons with a fire-box underneath, the whole mounted on a pair of wheels with axles and shafts for transportation by one horse. In some cases the cookers were on a more elaborate pattern so as to cook meat as well as soup. But a hot bowl of soup with bread or ration biscuits at the noon halt or at the end of a march, was a much appreciated comfort to the soldiers. The fuel used was good and the cookers were in operation during the march, so that a hot meal for the men was available as soon as a halt occurred. The portable cookers did away with that dismal wait after a long march when cold and tired troops have to suffer in chill discomfort until the camp kitchens are established and rations prepared in the ordinary way.

The success attending the general adoption of these cookers during the manoeuvres has resulted in special reports on them being called for by the War Office with a view to the preparation of a new pattern embodying the most advantageous features of the various designs. When completed a copy of the design and specifications will be furnished the Department of Militia and Defence. The portable cookers are comparatively inexpensive and would form a most useful portion of the equipment of every Canadian corps. Not only would they be available on the march or for advance parties going into camp, but on tactical field days or when bivouacking each unit could provide a hot meal for the men. This equipment would be particularly useful in large training grounds such as Petawawa, where the corps frequently have to proceed to distant areas for firing and manoeuvre. The units could remain at the distant areas all day without returning to camp at midday, thus saving time and horseflesh.

AIR CRAFT.

The Royal Flying Corps is recruited from all branches of the service and officers are seconded from their own corps for service with it. They wear a distinctive uniform. This corps was represented at both Inter-Divisional and Army Manoeuvres. A, squadron was detailed to either side for the Army Manoeuvres as well as two dirigible balloons. One aeroplane only was allotted to each division during the Divisional Manreuvres. (Normally, a squadron contains 12 aeroplanes.) Unfortunately during the mobilization of the air craft, and their flights from Salisbury and Aldershot to the points of concentration near Cambridge, two fatal accidents occurred. Two monoplanes collapsed in the air and their pilots and observers, four officers, were killed. This had the effect of bringing out an order from the War Office preventing the use of the monoplane during manoeuvres. Notwithstanding the reduction in the number of machines available for manoeuvres, the biplanes and dirigible balloons continued to carry out their duties, and the result was considered beyond expectations. Even where only one machine was available per division, the result was most satisfactory.

The first aeroplane order issued was of particular interest on account of the form adopted for this new branch. It was issued by the Red Commander on September 16. After a preliminary injunction to keep in touch with the cavalry, the order read: If possible the following flight will be made: Cambridge, Gallingay, Bigglesworth, &c., naming the different points to be visited. Next the air craft was instructed to obtain information (1) as to the position and direction of the march of the enemy’s columns; (2) as to any large bodies of troops in the vicinity of rail way stations; (3) as to the location of camps of the enemy; (4) as to whether there were any defensive positions being prepared on the Gog-Magog Hills, and the bridge between Linton-Saffron Walden, or the high ground above Chilly Hill, &c. The landing places were named up to a certain hour. It was the general opinion that the aeroplanes employed on strategically reconnaissance obtained as much information in three hours as would have taken a cavalry’ division three days to procure. (It was estimated that nearly 1,000 miles was covered by these air scouts in one day.) During the earlier phases of a campaign it is considered that aerial reconnaissance will have still greater effect when the opposing forces are approaching each other from greater distances than was the case in these manoeuvres. The air craft did not carry arms and no attempt was made to practice dropping dummy bombs or any other means of offence.

Kites were used during the cavalry manoeuvres owing to the high winds preventing the ascent of bi-planes or dirigibles during some periods of the operations. Guns were turned on the air craft upon several occasions and would probably have placed these machines in danger. The orders to the latter were to fly at a minimum height of 2,000 feet, otherwise they were ruled out of action. If they had to alight in the enemy’s country they were treated as neutral. In this connection it may be pointed out that according to the experience of Italian aviators in Tripoli, 2,000 feet is altogether too close for safety from rifle fire. An instance is recorded where a machine was badly shot-up at that distance and the observing officer wounded. On the night of the 18th September, the Blue dirigible ‘Gamma’ made a successful reconnaissance of the enemy’s position. She ascended from Kneesworth, Cambridgeshire, and made a long flight over the area of operations, locating the camps and bivouacs of both forces. As she passed she dropped ‘bombs’ in the shape of fireballs. She was quite invisible, and her presence could only be detected by the hum of her engines. The difficulty of distinguishing one’s own aerial scouts from those of the enemy was clearly brought out in these manoeuvres. The G.O.C. ‘Red’ Force is quoted as saying:—

‘The aeroplanes and dirigibles brought comfort and balm to his soul, but when the aircraft came and circled round his lunch table, as one did one day, and dropped a message on it, he really did not know whether it was one of his own aircraft with a message, or a hostile machine bent on his destruction.’ A remedy for this uncertainty must be found. It is not probable that nations will adopt machines of distinctive types, but some secret signal code must be adopted, or other solutions of this difficulty found.

Aeroplanes used during the manoeuvres were as follows:—

RED ARMY.

- Two 100 h.p. Breguets. (Captain Raleigh.)

- One Maurice Farman Biplane, 70 h.p. Renault. (Major Ross.)

- One B.E. 4, Aircraft Factory Biplane, 70 h,p. Gnome. (Lieut. Gordon Bell.)

- One B.E. 1, Aircraft Factory Biplane, 60 h.p. Renault. (Lieut. Longcroft.)

- One B.E. 5, Aircraft Factory Biplane, 60 h.p. Renault. (Lieut. Mackworth.)

- One Maurice Farman, 70 h.p. Renault. (Lieut. Longmore.)

BLUE ARMY.

- One B.E. 3, Aircraft Factory Biplane, 70 h.p. Gnome. (Lieut. Fox.)

- One short Tractor Biplane, 100 h,p. Gnome, (Commander Samson, R, N.)

- One B.E, 2, Aircraft Factory Biplane, 70 h.p. Renault, (Lieut., de Havilland.)

- One Aircraft Factory Biplane, (Lieut, Malone.)

- Several other machines would have taken part but for the order banning the use of monoplanes.

SIGNAL SERVICES.

During the Army Manoeuvres the wireless stations with the Blue Force were made up of Territorials and did good work. They apparently had not a proper system of code, and their messages were in some instances caught by the Red Force. Their operators were well qualified. The wireless waggon sets for communication between general headquarters and cavalry divisional headquarters were used at long ranges, showing the necessity for a powerful outfit. Several of these waggon sets were carried on motor vehicles during manoeuvres. This is quite possible where the roads are macadamized, but would not suit on roads of a sandy nature. The light Marconi sets designed for pack transport were invariably carried in light spring waggons in the same way as in Canada. The design of the pack loads, however, and their efficiency generally were highly spoken of. The cable waggon equipment has not changed materially and appears suitable for work on English roads. For work on heavy roads or rough country, parts of the waggon require strengthening. Six horses are required on heavy or hilly roads, though four are usually sufficient in England. The whole signal service is organized under one head, the Director of Army Signals, who is attached to army headquarters, taking his orders from the general staff. In this service are included the personnel not only for telegraph and telephone work, but also for visual signalling, motor cycles, bicycles and despatch riders. Regiments of Cavalry brigades of artillery and infantry battalions, retain control of their own signal services, but are assisted by the signal units as regards their training. In addition to the above mentioned signal services, a neutral service was organized for communication between the Chief Umpire and his staff of umpires. This was under a special Officer Commanding. They utilized the local lines of the country as far as possible, and special cable lines. It is understood that this service was a success.

SENIOR officers’ COURSE, At the School of Military Engineering.

The object of the Senior Officers’ Course at the School of Military Engineering, Chatham, is to encourage co-operation between the Engineers and other branches of the service; also to instruct Senior officers of all arms in the employment of engineering. The course consists of lectures, practical schemes of attack and defence on the ground, besides affording an opportunity to view and have explained to them various descriptions of field work, bridges, demolitions, redoubts, siege works, &c. A number of the lectures delivered at this course will be printed and distributed in Canada as well as in England for general information.

The military training of engineer units consists of two branches: 1. Technical training in their engineering duties in the field. 2. Training with other branches of the service in the field operations. Besides these two courses of military training engineers are employed as much as possible at their own trades so that the men will not be handicapped on their return to civil life. At present one of the principal duties of engineer units on these manoeuvres appears to be the organization of a water supply for all the troops in their own division, in co-operation with the medical services.

It was pointed out, however, during these lectures, that unless any technical difficulties arise, it is considered the duty of the Divisional troops themselves to provide their own water supply in the field. Field Companies do not carry a sufficient number of pumps on service to furnish water supply to their Division. On manoeuvres, Field Companies often leave behind some important stores to enable them to carry an additional number of pumps. It was, therefore, thought that manoeuvres are teaching the troops to rely too much upon the Sappers for their supply of water. In the demolitions which were carried out, gun-cotton was the chief explosive used, but a new fuze has taken the place of the old time and instantaneous fuzes. It is a combined time and instantaneous. If lit with a match, it burns as a time fuze, but when detonated with a commercial cap, its effect is instantaneous. Several attempts were made to destroy wire entanglements with the use of guncotton. Even when using a greater quantity than could be spared on active service, no appreciable result was obtained. It has been found that ordinary wire netting laid over wire entanglements, as a means of crossing, is more effective than an attempt at demolition.

HARNESS AND SADDLERY.

The artillery harness used is the breast-collar pattern similar to our own. Commanding Officers are in favour of mobilization harness and the issue harness being exchanged periodically so that the former may receive a certain amount of wear and not be issued new in event of mobilization. A belief exists that new harness deteriorates in store; also that horses should not be put to hard work in new harness until it has been “worked up” and softened.

A return is being made to the universal saddle in a slightly modified form. The seat is the same, but instead of the blanket being folded under the saddle and held in place by the numnah strapped to the arch and cantle, the side boards are sheathed in numnah felt and rest on the blanket which is folded on the horse’s back. In the case of most of the pack saddles seen, the load is carried too high on the horse’s back, the object aimed at being apparently to make the load as narrow as possible so as to take up a minimum of space on the road, rather than to facilitate the climbing powers of the animal over rough country. Men having experience with pack trains in our Canadian Rockies should be able to devise a much superior pattern of pack saddle.

In connection with the new universal saddle, it was noted that at Woolwich a method of storage is adopted that might be employed with advantage by our mounted units, especially where armoury accommodation is limited. The saddles, with blankets removed, are “nested” and suspended in rows from the ceiling in a compact mass. The remaining parts of the harness being suspended from the walls, a very considerable saving of space is effected.

TERRITORIAL TRAINING AND INSTRUCTION.

The training instruction of officers and N.C.O.’s of the Territorial Force is carried out at the School of Instruction at Chelsea Barracks for the London Division, and at the different regimental depots at centres throughout the Kingdom, where instructional facilities are available.

The Chelsea School of Instruction, which was visited, is under the command of an officer of the Brigade of Guards, assisted by an adjutant and instructors furnished by the same Brigade. The course of instruction is for a period of one month and consists of lectures and practical instruction in squad, company and battalion drill, at the close of which an examination is held and certificates awarded. The school is open as well to officers from the Overseas Dominion. The system of instruction appeared to be thorough and complete. The possession, by the school, of a model of a section of country facilitated the instruction in and study of minor tactics. While the courses of instruction were graded for the different ranks, facilities were afforded to an officer to qualify, not only for the command of a company, hut also for field rank if desired. Based upon the experience of the General Officer Commanding; the 1st London Division of the Territorial Force, concurred in by the commandant of the school, the best results so far as the qualification and general keenness and knowledge of officers were concerned, were to encourage the officer joining the Territorial Force to take a course of instruction at the outset of his career, lasting a period of at least three months, thus affording him a thorough grounding and begetting intelligent interest in his profession, which rendered any subsequent qualification for higher rank easy of acquirement.

It was ascertained that while as a general rule qualification for promotion before an officer could obtain a step in rank was advisable, in cases where a promotion might, with advantage to the service be made, prior qualification for each rank was not insisted on, but the officer so promoted was given the substantive increased rank, leaving him to qualify for such subsequent to his promotion, but within a reasonable time, each case being judged upon its merits.

There are two methods of obtaining instruction in musketry which qualify Territorial officers for promotion, and render them capable of giving instruction in musketry to their N.C.O.’s and men. These methods are:—

- Attendance at School of Musketry, Hythe.

- Attendance at local classes organized under divisional arrangements, and which are held at suitable and convenient centres.

These local classes were this year held at Edinburgh, Liverpool, Hampstead (for London), Chelsea and Hythe, and were carried on during the months of (a) April,

(6) September-October, in each case lasting for three weeks. The hours of instruction are arranged to suit the convenience of those attending and the work is therefore carried on late in the afternoon and in the evenings. The staff of the school consisted of one officer and six staff sergeants from the School of Musketry, Hythe, and the class consisted of 42 officers, divided into six squads, of seven each.

In conducting these classes arrangements are made for a drill hall, to be placed at the disposal of the Officer Commanding the course, and any necessary appliances not locally available are supplied from the Hythe School. The work in the drill hall is carried on with the object of showing Territorial officers how they can make the best use of the appliances, &c., at their disposal, and at the same time suggestions are made as to how drill halls can be improved for instructional purposes, and when necessary, what additional appliances should be provided.

On Saturdays work is carried out early in the afternoon, if possible away from the hall, so as to show some outdoor work in the way of judging distance and visual training, as well as indication, description and recognition of targets and aiming marks on the ground. This is done after instruction is given in the drill, by means of landscape targets. The instruction is very necessary to enable fire commanders correctly and rapidly to describe succinctly and clearly the targets or objects aimed at, so that the R. and F. may readily locate and distinguish them. Firing is seldom carried out on the service range, because the idea is to show how much can be done in drill halls, and besides the time occupied in the course is too short for much outdoor work. Before presenting themselves for a course of instruction, in order that full benefits may be derived from the course, officers are required to show that they have a working knowledge of essential parts of the Musketry Regulations.

The courses are regarded only as elementary, the objects being to qualify officers to train their companies in the drill halls and also teach them to train N.C.O.’s in their more elementary duties as fire unit commanders. If full advantage is taken of the knowledge of those officers who so qualify, and a good instruction system is arranged in regiments, much can be done to qualify N.C.O.’s and men in the essentials of musketry. The qualification of the officer should ensure that he is competent, and has a good working knowledge of the subject, as will enable him, without difficulty, to teach and instruct his men.

By attendance at these courses, including the lectures and practical work, instruction is given in:—

- Aiming, firing and trigger pressing.

- Mechanism, stripping and assembling of the rifle, and care of arms.

- Visual training, judging distances and standard tests.

- Fire discipline. Elementary direction and control of fire. Judging distance.

- The use of (a) miniature cartridge range; (6) the 25 or 30-yard range.

- Landscape targets, including the study of fire discipline and control.

- Use of various appliances.

- Elementary theory, paras. 146-175 of the Musketry Regulations.

Certain officers who have qualified at a local course, who can spare the time, and are desirous of further studying the subject, may be selected to attend the School of Musketry, Hythe, for a short advanced course. At this advanced course, these officers have fire field practices and also receive practical instruction in the conduct of range practices. Officers thus qualified are eligible for appointment as Regimental Musketry Instructors, and in the training of junior officers and N.O.C.’s in the duties they would have to carry out on service.

Spañard

.

Thanks for this excellent pair of blogs on the British 1912 manoeuvres. I found them of great interest as I have just published an article on the same subject, in the Journal of the |Society for Army Historical Research and am currently working on a book on the wider subject of British manoeuvres 1902-1914, The Canadian report is a great source I have not come across, and I would be very grateful if I could quote from it for the book. I would, of course, give you appropriate credit for putting me onto it. Please let me know if you would like a copy of my article on 1912.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank U for your kind words Mr Simon, not familiar just know the status quo recycled (Wiki), etc., accounts, turned the Original doc’s into text, which I’ve been holding under my top-hat for decades. I mainly cover, research, Canadian War History, owing too many inaccuracies and contradictions from past and present Historians/Authors, fallowing the status quo, corrections are in dire need. I only use prime, original documented archive sources, which is a good starting point, on my Blog, etc., supporting the facts from myths.

SVP Note: In certain Canadian accounts, I’m still clueless, and in overall world war history hard too remember all the details or know it all. Still learning with an open mind, certainly no writer, historian or is Canadian English a second language.

You may quote all etc., I have no issue, and provide U with the Cdn Gov published Book, Vol. No. year, p., etc., for the Maps I can send the pics without my Blog tag on them. I sent MSGs’ on T with link to Great War Forums, I posted both on one thread with snippets and Pics, etc., and sure some members with more leg work then I on this subject, will help.

With pleasure kindly, post your Article on Comment ‘ici,’ for students or interested individuals. Advised Original Documents on the British Army Manoeuvres are scarce.

Like stated the British War Office prepared a detailed report for BAM 1912, was supposedly official submitted to the Canadian Government, I haven’t found it, must be in the British Archives, No?

THK U FR YR TME.

Joseph

LikeLike

Joseph,

Thank you for your helpful response; I’m sorry I haven’t responded earlier but fitting writing the book in around my job doesn’t leave much time! The official report on the 1912 manoeuvres is indeed in the National Archives at Kew (TNA WO 279 / 47), along with those for all the pre-war manoeuvres, and is extremely detailed, but it is fascinating to get an outside view from the Canadian angle thanks to you. Incidentally, there is a story which one encounters in some books, eg Warner’s biography of Haig, though without adequate citation, that at the 1912 manoeuvres the Canadian Minister for War. Sam Hughes, got involved in a fist fight with the South African Minister of War and they had to be separated – all within sight of the King. I can’t find anything to back up this story but having read a little on Hughes it doesn’t sound impossible!

Simon

LikeLike

Mr. Simon, no need for sorrys’ or worries, I fully understand and assumed this was the case. The official submitted report to the Dominion of Canada on BAM 1912, could’ve gone up in smoke: Countless of old Canadian archives, doc’s etc., was lost in a fire many moons ago. In discussions concerning “Uncle Sam”, the wise Hughes’, was not the first or last altercation he had with “British Officers” or British Army officials etc. First, I heard of this, Hughes in fisticuffs with the South African Minister of War at the BAM 1912 next the King, “I can tell you why.”

Read first Paragraphs on Hughes and SSAW.

Lt. -Col. Sam Hughes’, Valcartier Camp, Birth of F.C. C.E.F. Battalions 1914.

http://wp.me/p55eja-D

The British sent Hughes packing back to Canada during the SSAW, and supposedly Sam awarded, gazetted, two Victoria Cross’s for his Heroic Gallantry, Lol. For years post SABW till1914, Hughes was still lobbing for those awards, with letters and requests to the British War Office, etc.

I’ll look into that Fight, however left out of the official CDN report.

THK U FR YR TME

Joseph

LikeLike

Hi professor Simon Batten, I sent U a @ and sent privet MSG on Twitter, Joseph Mad.. @NonNomen THK U FR YR TME. Joseph.

LikeLike